The Evolution of Blockchain and DLT

The Evolution of Blockchain and DLT

In 2008, the pseudonymous author (or authors), Satoshi Nakamoto, published the original Bitcoin paper, followed shortly thereafter by the first release of Bitcoin software in 2009. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the objective of Bitcoin was intended to create a decentralized currency that would remove traditional financial intermediaries – including governments, corporations and banks – from monetary transfers. In many ways, the introduction of Bitcoin was as much of a political and populist statement as it was the creation of a new digital asset.

To achieve the fundamental, decentralized mission of Bitcoin, Nakamoto wrote of the need for a trust-less, peer-to-peer (P2P) network that could provide auditable transactions and, thereby, ensure the integrity of ownership rights in this new digital asset. Hence, the blockchain was proposed.

WHAT IS OLD IS NEW AGAIN

While the attention to Bitcoin and other cyber-currencies has certainly increased the profile of the blockchain and distributed ledger technologies (DLT), broadly, Nakamoto did not originate the concept. The original Bitcoin paper, in fact, credits prior work published by Stuart Haber and W. Scott Stornetta in a 1991 research paper.

In the 1991 paper, Haber and Stornetta, working for the Bell Labs progeny, Bellcore, proposed the use of cryptographically-linked blocks in an append-only data structure. This would be used, they wrote, to irrefutably timestamp, version-control and notarize documents, including both textual and media files. The approach relied on the creation and storage of a cryptographically secure hash value derived from a current document, which would additionally be linked to hash values from immediately preceding documents in order to ensure the integrity of the data lineage. The blocks would, themselves, also be digitally signed with private keys. Collectively, this would allow one to prove that a specific version of a document existed at a specific time.

Haber and Stornetta referred to the core system component as a Time Stamp Server (TSS), and the association between sequential data blocks as “linking”. They also highlight the need for distributed trust across a network of TSS engines, in order to protect data integrity from a rogue instance. If this all sounds a bit familiar to those who’ve followed the evolution of Bitcoin, it’s because it is precisely the approach used by the underlying blockchain to sign and append records.

The document-centric use-case proposed remains highly relevant, even today. The approach is especially applicable to cases where the risk of document tampering and document fraud must be mitigated, such as for intellectual property rights, transfers of ownership and contract arbitration.

Importantly, this earlier work by Haber and Stornetta also highlights that the technology behind blockchain is not new. In fact, many similar concepts were also incorporated into what was one of the earliest, and certainly most notorious P2P platforms to date: the music-sharing network, Napster, which launched in 1999. While Napster and its descendent, BitTorrent, did not seek to provide a ledger, they did shard and distribute files as digitally signed data blocks that could later be sequentially restored by coordination across several peer network hosts.

What has changed most significantly from these earlier examples, however, is the proliferation and speed of broadband networks, coupled with access to voluminous and inexpensive amounts of compute and storage now available on the cloud. Together, this infrastructure allows for the kind of scale, horsepower and democratization that is ideally suited to a cryptographically-enabled P2P platform, like blockchain.

TRACKING THE HYPE-CYCLE FOR DLT

While cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin, have generated both praise and admonishment amongst pundits, corporations, academicians and public policy makers, interest in DLT as a transformational technology has been somewhat less circumspect, though it too has had its share of advocates and detractors.

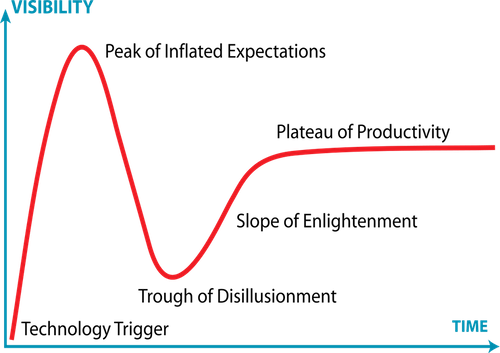

Like many new technologies – and putting aside, for a moment, the fact that the concepts behind the blockchain are not new – DLT has traversed the typical hype cycle, first developed by Gartner to represent the maturity, adoption and application of a specific technology. An initial rise in inflated expectations, some of which continue to proliferate, is often followed by a trough of disillusionment as actual experiences fail to match the hype. For blockchain, this downward trend is perhaps best captured by a 2019 Gartner paper which declared “blockchain fatigue”, due to some early failures in supply chain applications.

Personally, I’ve sat in on more than a few meetings that all but declare the blockchain as a purveyor of world peace! At times, companies have promoted DLT solutions as a marketing gimmick to drive commercial interest, capital investments, valuations or all of the above. This is not unusual. Throughout my career, I’ve witnessed firms apply cutting-edge technology buzz-words and marketing campaigns to legacy applications. And, while some of these declarations may seem uninformed, if not disingenuous, the truth is that there is real, and as yet largely untapped value in DLT.

As with any transformational technology, of course, value must be refined and significant challenges overcome. In hype-cycle parlance, these steps lead from the trough of disillusionment towards the slope of enlightenment.

MADE FOR THE DIGITAL ECONOMY

As a backdrop to the DLT journey, the dynamics of an increasingly digital economy are first worth considering. On the one hand, many might assume that a byproduct of a digital economy is greater integration amongst participants, resulting in a more cohesive, unified experience. This is largely true, and is evidenced by the ways in which partners and consumers now interact with digital properties and supply chains, often via aggregated portals, standard protocols, and open APIs.

Yet, at the same time, the digital economy has also driven greater fragmentation. Consider the number of new businesses that have launched in the last few years and the increase in gig workers powered by the global breadth and reach of the Internet, broadband access, smartphones and cloud computing. Companies, today, are also less likely to be the fully vertically-integrated and self-contained organizations of yesteryear, and are more apt to focus on core-competencies and outsource the rest. As a result, some also refer to this as the “sharing” economy.

So, how can a unified experience and increased fragmentation both be true? Witness companies like Uber and Airbnb, two newer behemoths in the transportation and lodging sectors that own none of the underlying automotive or real estate assets. Leveraging the network effect of the digital economy, these firms provide a unified client experience, while leveraging a federated and growing supply chain largely consisting of individuals and small businesses.

At the core of all of this is the lineage and flow of data between, and amongst a collection of complimentary, but otherwise trust-less parties. In short, this opportunistic cohort is a byproduct of the digital, or sharing economy and it is what makes DLT so compelling as a mutualized platform. As for the most obvious challenges with more widespread DLT adoption, they can be broadly characterized as technical, participatory and incentives-related issues.

DLT IN FINANCIAL SERVICES

In financial services, for example, discussions about the disintermediation of custody banks and central security depositories (CSDs) have long drawn attention, almost since the inception of the blockchain. The reality, however, is that the penetration of existing industry infrastructure and regulatory constraints represent some significant, even if ultimately surmountable hurdles.

This is especially true in more liquid markets, where data and transactional flows tend to be more mature, standardized and efficient. As such, adoption in this use-case necessitates significant technical change and broad industry participation. Incentives may also be misaligned, as some participants may fear disintermediation or may be too tightly wed to legacy systems and processes that require a costly makeover. Even so, use cases like corporate actions, transfers, proxy voting and investor communications seem like good candidates for DLT.

In private markets, in loan origination, and in less liquid OTC markets, however, more immediate opportunities may exist. In part, this is because data lineage and flows are more fragmented in these markets, often following a paper trail. There’s also a broad network of participants and no dominant, truly mature platform.

Clayton Christensen’s 1997 book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, presents a seminal theory of “disruptive innovation”. Christensen details how underserved consumers, or market segments are typically more ripe for innovation, especially when established incumbents fail to address their needs. In many ways, this is the current state of the private and OTC markets, so incentives to adopt transformational technologies, like DLT, are far more closely aligned amongst participants.

Recently, Vanguard partnered with fintech provider, Symbiont, on the launch of a DLT pilot designed to digitize the collateralization, origination, settlement and servicing of asset-backed securities (ABS). The pilot also included a large, unnamed US-based ABS issuer, as well as collaboration with BNY Mellon, State Street and Citi. This was not Vanguard’s first foray into DLT, having also worked with Symbiont on a 2017 initiative to better manage index data, as well as on a separate P2P foreign exchange platform.

Similarly, fintech Inveniam Capital Partners is collecting, validating, digitizing, indexing and notarizing static and time-series data that is attributable to private and less liquid assets. Much of this data, today, is maintained on a litany of spreadsheets and in fragmented paper trails. Inveniam’s platform helps pave the way for increased digital tokenization of these assets on a DLT. Importantly, the availability of such data also reduces investment risk and increases price transparency. In some cases, it may additionally allow Level 3 assets, considered the least liquid and most difficult to value under FASB 157, to be reclassified as more liquid Level 2 assets. This would have a profound and positive impact on liquidity, valuation and balance sheets. Currently, Inveniam is focused on commercial loans, CMBS and thinly-traded munis.

A number of fintechs are also working on the application of DLT for residential mortgage origination and servicing. Here, again, the value proposition of DLT is clear, given the volume of loans and number of parties involved in origination, underwriting, legal, titling, insurance, servicing and securitization. Remarkably, much of the mortgage process, today, still remains document-centric and highly manual, with emails, fax and paper serving as primary conduits for data exchange. To date, no dominant player has yet emerged to drive this necessary transformation, in part due to the sizable fragmentation and lack of technical proficiency amongst the many participants, but the eventual adoption of a DLT solution seems ideally suited.

There are, of course, other examples of inflight, pilot, or early production DLT initiatives within the financial services industry, beyond cryptocurrencies, and I anticipate that investment in the technology will continue.

REACHING THE PLATEAU OF PRODUCTIVITY

To be most effective, DLT solutions should be mutualized across a critical mass of participants. To pursue in-house DLT initiatives that are governed by a single body, or only intended for internal use is clearly less impactful, and generally more difficult to justify. In those cases, there are frankly other technologies that may be a better fit, while offering less risk and greater performance – an improving, though recognized pain point of some DLT platforms. There are also hybrid architectures that leverage DLT for tokenization, multi-party transactions and auditability, while using off-chain technologies to house more extensive reference and supporting data.

Most importantly, the early euphoria around the blockchain and DLT is increasingly giving way to more pragmatic consideration. On the hype-cycle, this continued progression will eventually achieve a plateau of productivity. No, the technology is not the answer to every data, trust or supply-chain problem within financial services or other industries. But, the use-cases and emerging production implementations, along with current technical limitations, will most certainly continue to evolve and will ultimately deliver real, if not transformational value.

About Author

Gary Maier is Managing Partner and Chief Executive Officer of Fintova Partners, a consultancy specializing in digital transformation and business-technology strategy, architecture, and delivery within financial services. Gary has served as Head of Asset Management Technology at UBS; as Chief Information Officer of Investment Management at BNY Mellon; and as Head of Global Application Engineering at Blackrock. At Blackrock, Gary was instrumental in the original concept, architecture, and development of Aladdin, an industry-leading portfolio management platform. He has additionally served as CTO at several prominent hedge funds and as an advisor to fintech companies.